Robert Propst:

Utopian Technocrat

Amy Auscherman

Find the common thread among the following objects: pad for menstrual discharge; vertical timber harvester; wine preserver and pourer; citrus picker; self-making bed; livestock identification system. Can’t? All were speculative product designs explored by sculptor, inventor, cattle rancher, designer—or as he liked to be referred to— “searcher,” Robert Propst.

While his name may not be familiar, his most innovative and successful design is so ubiquitous that every workplace of the latter 20th and early 21st centuries owes something to its conception. Action Office II (AO2), a modular, reconfigurable system of panel-based walls, surfaces, and storage was developed by Propst for furniture company Herman Miller and introduced in 1968. Many would recognize the cubicles Propst’s invention became, but the intent of his design was to unlock the potential of white-collar workers, not frustrate it. Propst had a utopian vision for the office that was opposite of the corporate hellscape it became. After his research identified the value of body movement and rest, an early design for Action Office (AO) even included a portable mat for “supine postures,” or in other words, naps. As he recounted towards the end of his life, “Not all organizations are intelligent and progressive. Lots are run by crass people. They make little, bitty cubicles and stuff people in them. Barren, rathole places.”

From management of menstrual cycles to management of information flow in an office, Propst approached perceived design problems with his genius-level IQ and astringent disdain for the status-quo. In 1958, he was hired to lead the Herman Miller Research Division (HMRD) and established an office in Ann Arbor, Michigan. By this time, the post-war sales boom of residential furniture by the likes of Charles and Ray Eames, George Nelson, and Isamu Noguchi had plateaued leaving Herman Miller searching for opportunities to diversify its revenue. Propst was instructed to look for opportunities to innovate outside of the furniture industry, but quickly found a worthy problem to solve. Deeply dissatisfied with his own working environment, furnished by Herman Miller, Propst began to reinvent the office itself.

After World War 2, and with the growth of global communications, the explosion of knowledge workers—a term coined by management consultant Peter Drucker—rendered most workplaces obsolete. “The office is a place where we go to suffer a variety of environmental accidents,” Propst wrote. Packed steno pools surrounded by private executive offices didn’t support the kinds of complex tasks and information processing that were becoming the norm in the white-collar workplace. To mitigate this new reality, the HMRD undertook years of behavioral research to understand what “human performers” need to do their most inspired work. Propst drew from leading figures in psychology, sociology, and the sciences to infuse his approach with a recognition of the most important and least understood inhabitant of the new workplace: the human brain. The office, he posited, is above else “a mind-oriented living space.”

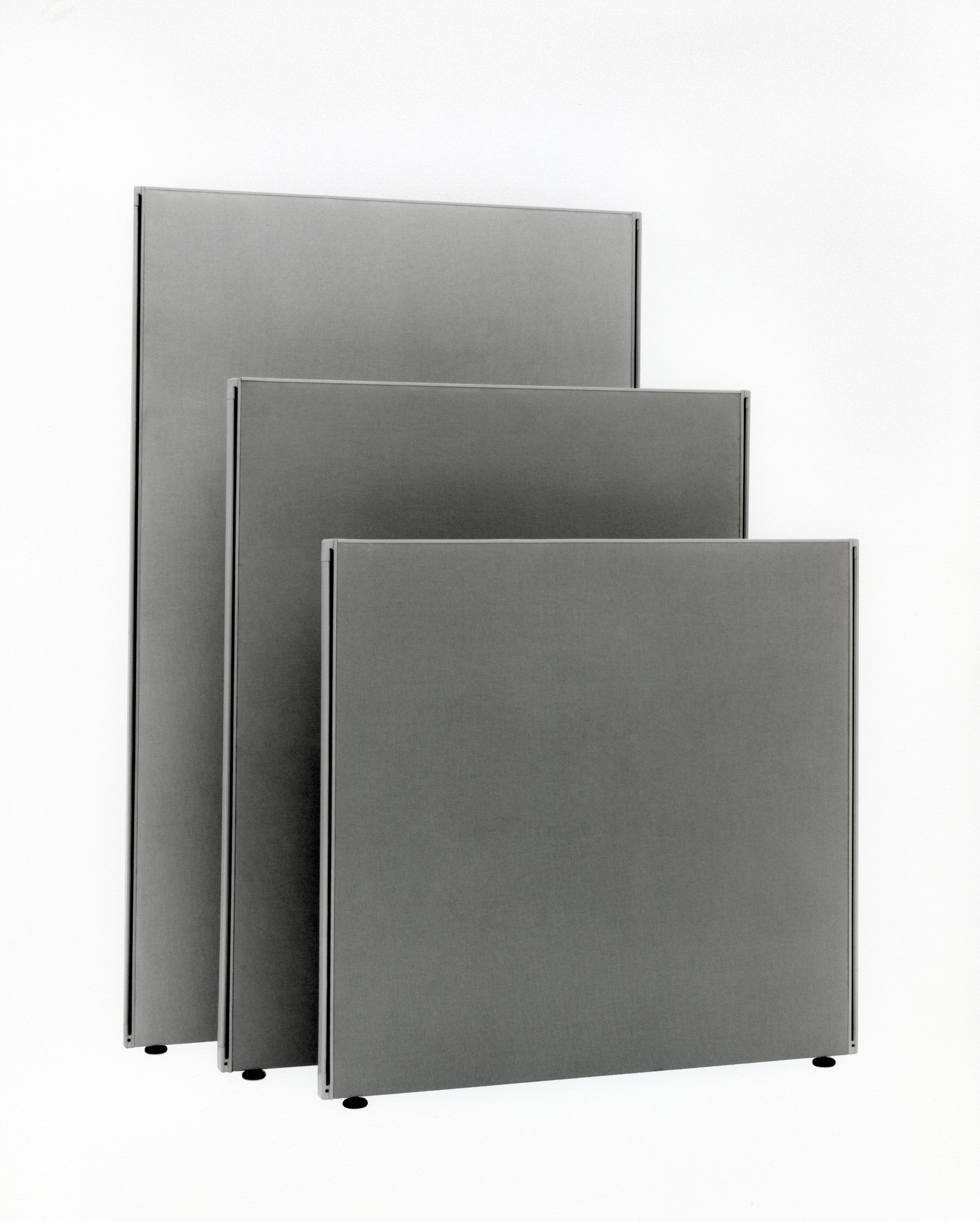

With the goals of “health and productivity in the office,” Propst worked with George Nelson to design a system of freestanding furniture that would fulfill this promise. Introduced in 1964, Action Office I (AO1) was comprised of a variety of worksurfaces, seated and standing desks, storage, and perch seating. While the furniture garnered significant press, it proved difficult to manufacture and overly expensive. Moreover, it was still just furniture. The commercial and intellectual failure frustrated Propst and sent him back to the proverbial drawing board—this time without Nelson. HMRD refocused its efforts to develop a more operational version of AO that relied on free-standing, interlocking panels to divide and establish space. The panels supported components like desks, shelves, and storage while also creating varying degrees of enclosure and privacy for office workers. It was easy to install, flexible enough to quickly reconfigure, and was a fraction of the cost of AO1. Herman Miller transformed a disused bank into a “learning center” to host Propst-led seminars and demonstrate the revolutionary product to potential clients. Charles Eames may have dubbed it “honest ugly,” but AO2 quickly reshaped the American workplace—and even spawned “Facility Management” as a field of study and professional activity.

However, the design revolutions that lead to the commercial success of AO2 also had unintended consequences. While Propst sought to eliminate the notion of the all-knowing designer by drawing from behavioral sciences and allowing end users to shape their own ideal workspace through a modular system, these capabilities were instead co-opted by businesses—with more of an eye on efficiency, floorplate metrics, and the bottom line. When electric wiring was added to the system in the late 1970’s Propst saw the writing on the wall. Once it was wired, another barrier was erected against the original idea of reconfiguration and rearrangement. Tools of empowerment had become tools of entrapment.

Recent explorations by students of SAIC’s Whatnot Studio offer reminders of AO2’s cautionary tale. Rio Chen’s take on the state of Ultimate Happiness evokes a similar neoliberal attempt at systematized corporate health and well-being—all wrapped up in a delicious, well-designed, and wasteful package. EULA by Sam Link and Tim Karoleff is strikingly similar to a panel offered in a later iteration of AO2. The diffracted form affords the user privacy and the promise of natural lighting, but cuts off the outside world and distorts the reality of what lies beyond. As students of design, we should not squander the notion that each act of design contains within it the potential to do or make something better. But as a historian may warn, even with the best intentions, design is susceptible to domino theory. New problems can be created as easily as old ones are solved. Ultimately, we may be reminded that design—and by proxy Utopia—is best understood as a quest, not a destination.

Whatnot Studio

Whatnot Studio